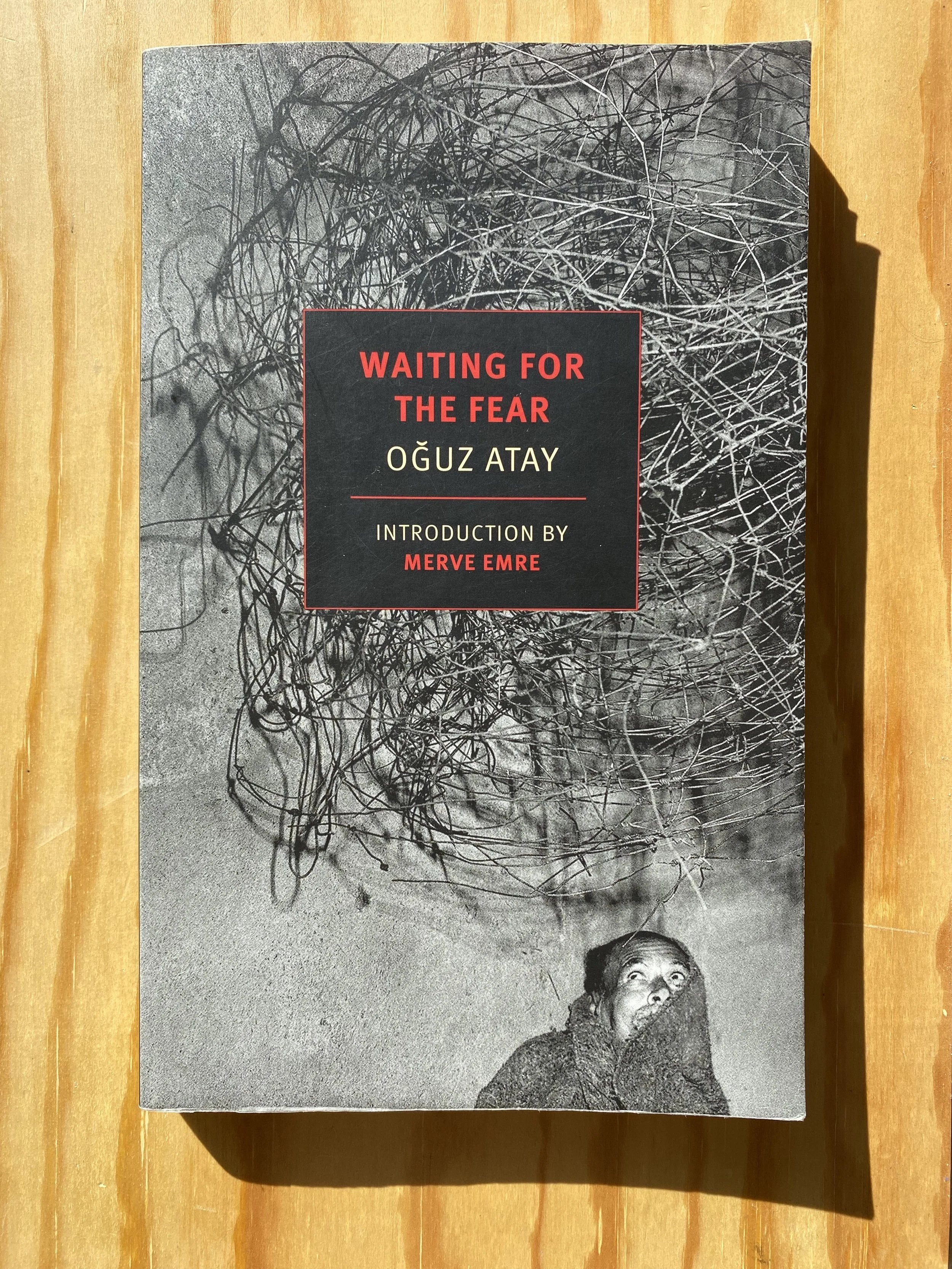

3/5 stars

What's it about? In this eerie collection, the stories of Turkish writer Oguz Atay catch folks in disturbing situations, such as discovering the desiccated body of an ex in the attic or receiving a threat in an alien language.

How’d I find it? I must credit the NYRB Classics Book Club for this find.

Who will enjoy this book? If you like the stories of Samanta Schweblin or Anna Kavan, Waiting for the Fear will be right up your alley.

What stood out? Atay favors an imperious tone that brightens these dark tales. The speakers and protagonists of the stories in Waiting for the Fear react to strangeness in manic and paranoid ways. Take, for example, the advice columnist of “Not Yes Not No” who composes a deranged reply to a lovelorn man lacking in letter writing skills: “How can someone so pitiful feel such self-confidence?”

Which line made me feel something? From the title story: “The moon incident had gotten me thinking that I used to dislike nature, but now I wondered if I’d always sort of liked it. I wondered if at some point, because of the trees, the grass or insects that can’t fly, I’d begun in fact to love it.”